Arguably the issue at the forefront of most commercial real estate investors’ minds is that of inflation and what it means for their investment strategy, target assets and target returns. Over the course of three articles we analyse inflation in Asia Pacific, highlighting current trends as well as opportunities, challenges and potential strategies for investors. In the first article, we focussed on inflation trends across the region. In this second article we analyse prime office fundamentals in an inflationary environment.

Property as an inflation hedge is not clear-cut

While commercial real estate is often seen as a hedge against inflation, the issue is not necessarily that clear cut. The general view is that unlike fixed income assets such as bonds, the income returns in commercial real estate (i.e. rent) can fluctuate with the market – therefore yields are real rather than nominal. Although this is true, a true inflation hedge moves in tandem with inflation, rather than keeping pace over time. Within the current context, that depends on the ability for landlords to push through rental growth, which is affected by exogenous factors. Primarily, the position in the market cycle is a key determinant – low vacancy and high demand would be supportive of rental growth whereas the opposite would not. Furthermore, the cause of inflation must also be considered. The optimum situation would be is if inflation is driven by strong economic growth, the so called “demand-pull”. However, if inflation is due to increasing cost pressures amid weakening economic growth, “cost-push”, then this is likely associated with greater caution, lower demand and less ability to lift rents. Then there is asset-level variation: not all assets perform in the same way within the same market. As such there is considerable nuance in using property as an inflation hedge and even in a global pandemic, the importance of local context is paramount.

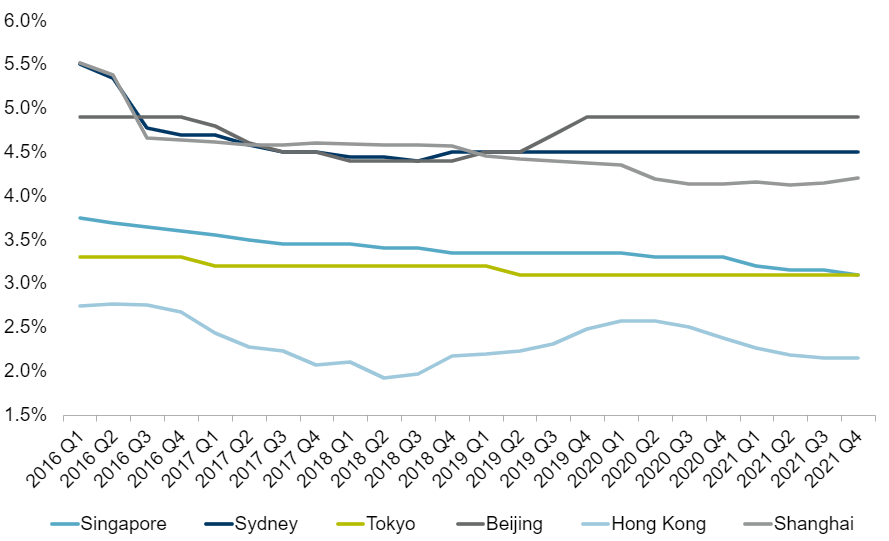

Prime yields are cyclical lows

Arguably the greatest driver of prime office value growth prior to the pandemic has been through yield compression. In Asia Pacific major gateway markets, prime office yields compressed by as much as 120bps over the three years prior to the pandemic. Asset pricing to book value saw much steeper compression. Primarily this was the product of declining hurdle rates, increased competition for quality assets as dry powder capital set new record levels and institutional investors simultaneously making greater target allocations to real estate.

Figure1: Prime office yields for select markets, 2016-2021

Source: Cushman & Wakefield

Moving forward to the present, core office buildings in major gateway markets remain in demand. Recent transaction evidence shows that pricing has been maintained through the pandemic as investors have targeted both their defensive and growth qualities. Longer weighted average lease terms, blue chip tenants and flight to quality by occupiers all help drive security of income for these assets.

However, with interest rates forecast to trend upwards and property-bond yield spreads around long-term averages for much of the region, it suggests that property yield compression has largely run its course, at least at the market level. Positively, little upward pressure is also expected with spreads able to compress further and remain off long-term lows. Inevitably, attention therefore turns to income growth to boost returns.

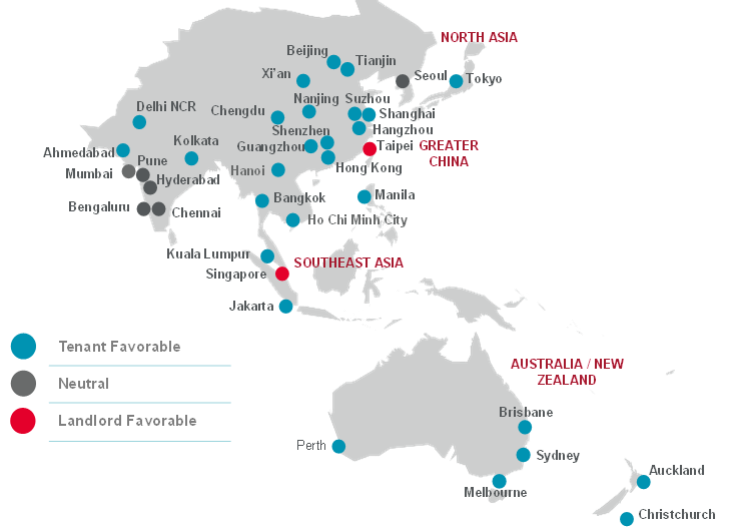

Office markets currently tenant favourable, but recovering quickly

Note: Indicative of Conditions in overall market

The Asia Pacific office market has shown remarkable resilience, being the only region to record consecutive quarters of positive net absorption since the onset of the pandemic. Office demand for the full year in 2021 across Asia Pacific’s top 25 markets rebounded to 64 million square feet (msf), which is 60% above 2020 levels. This is due to record demand in Tier 1 markets in mainland China. Demand is expected to increase further to 72 msf—reflective of a stronger recovery and office employment growth across the entire region—before returning to pre-pandemic levels of around 83 msf in 2023. At the regional level, projected employment growth and the transition to a higher proportion of office-based employment are forecast to more than offset the underlying headwinds from remote working. With this, the nature of demand will shift, though, with corporates placing a greater emphasis on building quality and amenity.

Rents are forecast to reach trough in late 2021 through to early 2022 in most markets. The main exception being Tokyo which is forecast to experience more prolonged rental decline partly due to supply increases resulting from long-term urban redevelopment projects in central locations. Again, this reinforces that in many markets the window of opportunity is closing earlier than anticipated for occupiers. However, forecast rental growth is expected to be relative muted over the next five years and few gateway markets are likely to see rental growth outstrip inflation over the same period.

Figure 2: Prime CBD rental growth against inflation (% p.a.), Q4 2021 - Q4 2026

Source: Moody’s, Cushman & Wakefield

Against this rental backdrop, Singapore, Australia’s eastern seaboard markets and Hong Kong appear most investor friendly. At least for core investors seeking more passive asset management strategies. Singapore rebounded strongly in H2 2021, turning landlord friendly in the last quarter of the year. Vacancy remains tight, which combined with relatively limited supply is forecast to drive rental growth of almost 5% per annum through to 2025. The market also benefits from comparatively short lease duration (at 3 years) allowing landlords frequent opportunities to reset lease terms to market value. Hong Kong has endured a longer downturn but appears poised for recovery with rents forecast to start increasing from next year.

Within the regional context, Australia’s inflation outlook is quite muted at around 2.5% per annum through to 2025. In comparison, rent growth is forecast at over 4% per annum in Melbourne and Sydney, with prime rents in Melbourne being driven by the recent influx of high-quality stock. An element of caution is required, though, as the strongest rent growth in these markets is forecast to occur towards the end of the forecast period. However, longer lease length (of five years) together with annual rental escalations which form part of standard lease terms in Australia and can be tied to, or above, inflation should help offset weaker near-term growth.

Elsewhere occupier conditions are likely to be more challenging – as new supply is forecast to keep vacancy elevated and contain rental growth, even in markets with robust demand such as in India and mainland China. This is not to say opportunities are not available in these markets, especially for core assets which are expected to attract the majority of future tenant demand. Rather, that they may require more discerning asset targeting and/or more active asset management strategies. While delivering a value-add strategy is more complex than a straight core approach there is scope in the current climate, not least with the greater focus on environmental and sustainability performance credentials. We focus on this issue in the third and last article of the series.